If you wish to contribute or participate in the discussions about articles you are invited to contact the Editor

Galileo Space Segment

| GALILEO | |

|---|---|

| Title | Galileo Space Segment |

| Author(s) | GMV |

| Level | Basic |

| Year of Publication | 2011 |

The Galileo global component will provide the GALILEO Space segment: a constellation of Galileo satellites, each of which will broadcast navigation timing signals together with navigation data signals which will contain not only the clock and ephemeris correction data essential for navigation but also integrity signals which provide a global space-based augmentation service.

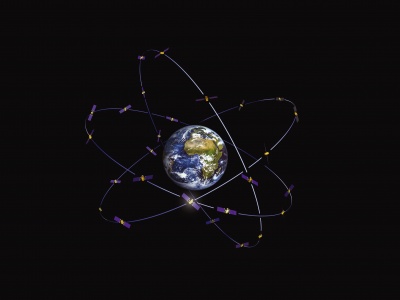

The GALILEO space segment will comprise 30 satellites in a Walker constellation with three orbital planes at 56° nominal inclination.[1] Each plane will contain nine operational satellites, equally spaced, 40° apart, plus one spare satellite to replace any of the operational satellites in case of failures. The orbit altitude of 23 222 km results in a repeat a constellation repeat cycle of ten days during which each satellite has completed seventeen revolutions.

Constellation features

The altitude of the satellites has been chosen to avoid gravitational resonances so that, after initial orbit optimisation, station-keeping manoeuvres will not be needed during the lifetime of a satellite. The altitude chosen also ensures a high visibility of the satellites.

The position constraints for individual satellites are set by the need to maintain a uniform constellation, for which it is specified that each satellite should be within +/- 2° of its nominal position relative to the adjacent satellites in the same orbit plane and should be within 2° of the orbit plane.

The in-plane accuracy is equivalent to a relative tolerance of over 1000 km but requires very careful adjustment of the satellite velocity to ensure that the orbit period of all the satellites is kept precisely the same. The across-track tolerance allows the inclination and RAAN of each satellite to be biased at launch so that natural drifts remain within the tolerance without the need for orbit plane changes requiring major expense of fuel.

The spare satellite in each orbit plane ensures that in case of failure the constellation can be repaired quickly by moving the spare to replace the failed satellite. This could be done in a matter of days, rather than waiting for a new launch to be arranged which could take many months. The satellites are designed to be compatible with a range of launchers providing multiple and dual launch capabilities.

There are good reasons for choosing such a structure for the Galileo constellation. With 30 satellites at such an altitude, there is a very high probability (more than 90%) that anyone anywhere in the world will always be in sight of at least four satellites and hence will be able to determine their position from the ranging signals broadcast by the satellites. The inclination of the orbits was chosen to ensure good coverage of polar latitudes, which are poorly served by the US GPS system.

From most locations, six to eight satellites will always be visible, allowing positions to be determined very accurately – to within a few centimeters. Even in high rise cities, there will be a good chance that a road user will have sufficient satellites overhead for taking a position, especially as the Galileo system will be interoperable with the US system of 24 GPS satellites.

Galileo satellites

The Galileo constellation is composed of a total of 30 Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) satellites, of which 3 are spares, in a so-called Walker 27/3/1 constellation. Each satellite will broadcast precise time signals, ephemeris and other data. The Galileo satellite constellation has been optimised to the following nominal constellation specifications:[2]

- circular orbits (satellite altitude of 23 222 km)

- orbital inclination of 56°

- three equally spaced orbital planes

- nine operational satellites, equally spaced in each plane

- one spare satellite (also transmitting) in each plane

The Galileo satellite is a 700 kg/1600 W class satellite.

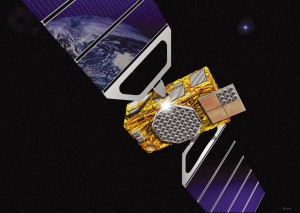

The image shows an artist's impression of a Galileo spacecraft in orbit with solar arrays deployed. The spacecraft rotates about its Earth-pointing axis so that the flat surface of the solar arrays always faces the Sun to collect maximum solar energy. The antennas, shown on the underside of the body in the picture, always point towards the Earth. The spacecraft body will measure 2.7 m x 1.1 m x 1.2 m and the deployed solar arrays span 13 m.

Galileo Satellite components

The L-band antenna transmits the navigation signals in the 1200-1600 MHz frequency range.

The SAR (Search and Rescue) antenna picks up distress signals from beacons on Earth and transmits them to a ground station for forwarding to local rescue services.

The C-band antenna receives signals containing mission data from Galileo Uplink Stations. This includes data to synchronise the on-board clocks with a ground-based reference clock and integrity data which contains information about how well each satellite is functioning. The integrity information is incorporated into the navigation signal for transmission to users.

Two S-band antennas are part of the telemetry, tracking and command subsystem. They transmit housekeeping data about the payload and spacecraft to ground control and, in turn, receive commands to control the spacecraft and operate the payload. The S-band antennas also receive, process and transmit ranging signals that measure the satellite's altitude to within a few metres.

The infrared Earth sensors and the Sun sensors both help to keep the spacecraft pointing at the Earth. The infrared Earth sensors do this by detecting the contrast between the cold of deep space and the heat of the Earth's atmosphere. The Sun sensors are visible light detectors which measure angles between their mounting base and incident sunlight.

The laser retro-reflector allows the measurement of the satellite's altitude to within a few centimetres by reflecting a laser beam transmitted by a ground station. The laser retro-reflector is used only about once a year, as altitude measurements via S-band antenna ranging signals are otherwise accurate enough.

The space radiators are heat exchangers that radiate waste heat, produced by the units inside the spacecraft, to deep space and thus help to keep the units within their operational temperature range.

Interior: payload

A passive hydrogen maser clock is the master clock on board the spacecraft. It is an atomic clock which uses the ultra stable 1.4 GHz transition in a hydrogen atom to measure time to within 0.45 ns over 12 hours.

A rubidium clock will be used should the maser clock fail. It is accurate to within 1.8 ns over 12 hours.

The spacecraft has four clocks, two of each type. At any time, only one of each type is operating. Under normal conditions, the operating maser clock produces the reference frequency from which the navigation signal is generated. Should the maser clock fail, however, the operating rubidium clock will take over instantaneously and the two reserve clocks will start up. If the problem with the failed maser clock is unique to that clock, the second maser clock will take over from the rubidium clock after a few days when it is fully operational. The rubidium clock will then go on stand-by or reserve again. In this way, by having four clocks, the Galileo spacecraft is guaranteed to generate a navigation signal at all times.

The clock monitoring and control unit provides the interface between the four clocks and the navigation signal generator unit (NSU). It passes the signal from the active master clock to the NSU and also ensures that the frequencies produced by the master clock and the active spare are in phase, so that the spare can take over instantly should the master clock fail.

The navigation signal generator, frequency generator and up-conversion units are in charge of generating the navigation signals using input from the clock monitoring unit and the up-linked navigation and integrity data from the C-band antenna. The navigation signals are converted to L-band for broadcast to users.

The remote terminal unit is the interface between all the payload units and the on-board computer.

Interior: service module

SADM is the drive mechanism that connects the solar arrays to the spacecraft and rotates them slowly so that the surface of the arrays can remain perpendicular to the Sun's rays at all times.

The gyroscopes measure the rotation of the spacecraft.

The reaction wheels control the rotation of the spacecraft. When they rotate, so does the spacecraft. It rotates twice per orbit to allow the solar arrays to remain parallel to the Sun's rays.

The magneto bar modifies the speed of rotation of the reaction wheels by introducing a torque (turning force) in the opposite direction.

The power conditioning and distribution unit regulates and controls power from the solar arrays and batteries and distributes it to all the spacecraft's subsystems and payload.

The on-board computer controls all aspects of spacecraft and payload functioning.

Launching and phases

ESA will launch the first four operational satellites using two separate launchers. The first two satellites will be placed in the first orbital plane and the second in the second orbital plane. These four satellites, plus part of the ground segment, will then be used to validate the Galileo system as a whole, together with advanced system simulators. Then, the next two satellites will be launched into the third orbital plane. They will be followed by several launches with Ariane-5 or Soyuz from the Europe’s Space Port in French Guyana. The first services will be delivered when the constellation has reached its Initial Orbital Configuration. When the 30 satellites are in space on all its three orbital planes, Galileo will be fully operational, providing its services to a wide variety of users throughout the world.

The assembly of the first four satellites in the future constellation, which will be launched in 2011-2012 as ESA has confirmed, is currently being completed. The creation of the terrestrial element of the infrastructure is continuing in parallel; this involves choosing sites and building a large number of stations spread across a number of countries and regions of the world: Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, New Caledonia, Réunion, French Guyana, Tahiti, Sweden, Norway, the United States, Antarctica (Troll, Adélie Land), etc.

Work on the deployment phase was launched in 2008 and is proceeding actively. This work has been divided up essentially into six packages, each of which is the subject of a public procurement procedure. Competitive dialogue with the tendering firms is a key element in the procedures which have been launched. As a result, the first four contracts, with a total value of around € 1 250 million, were awarded in 2010; they are for the packages covering system engineering support, satellite construction (with an initial order for 14 satellites), launchers (for the launch of 10 satellites, but with options for additional launches) and operations, respectively. The other two packages, relating to ground infrastructure, will be awarded in 2011. The contracts for additional equipment and facilities will also need to be awarded in the course of 2011.

The public procurement contracts already awarded are enabling the Commission to adjust its approach to meet the deadline of 2014. Accordingly, the development and deployment phases will continue in parallel until 2012, when the development phase will be completed, and the exploitation phase for the first services will start in 2014. A first stage will be the partial commissioning of the infrastructure (initial operational capability, or IOC) as from 2014-2015 and the provision of the open service, the search and rescue service and the PRS. At this stage, however, accuracy and availability will not yet have reached their optimum levels.

The European GNSS has one prime advantage over other systems: it is the only one designed for civilian purposes and under civilian control. It has other potential advantages which should not be disregarded, such as its commercial service, which might make it possible to authenticate signals and further improve the accuracy of the open service. Finally, its open service complements, and is interoperable with, the American GPS, so that the combined use of the two systems will afford a degree of reliability and accuracy which is likely to fulfil most users' needs worldwide in the mass applications market. However, most of these benefits will materialise only after the full infrastructure is complete. Galileo's Full Operational Capability (FOC) should be achieved in 2019-2020. It might change, depending on availability of financing, technical problems and industrial performance.[3]