If you wish to contribute or participate in the discussions about articles you are invited to contact the Editor

Two-body Problem: Difference between revisions

Jaume.Sanz (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Jaume.Sanz (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

::{| | ::{| | ||

|+align="bottom"|'' | |+align="bottom"|''Figure 1: GNSS satellite orbital elements'' | ||

| [[File: Two_Body_Orb.png.png|none|thumb|400px|frameless]] | | [[File: Two_Body_Orb.png.png|none|thumb|400px|frameless]] | ||

| [[File: Two_Body_Orb_2.png|none|thumb|400px|frameless]] | | [[File: Two_Body_Orb_2.png|none|thumb|400px|frameless]] | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

::[[File:Two_Body_Eliptj.png.png |none|thumb|400px|'''''Figure 2:''''' Elliptic orbital representation | ::[[File:Two_Body_Eliptj.png.png |none|thumb|400px|'''''Figure 2:''''' Elliptic orbital representation.]] | ||

Revision as of 07:05, 23 January 2012

| Fundamentals | |

|---|---|

| Title | Two-body Problem |

| Author(s) | J. Sanz Subirana, J.M. Juan Zornoza and M. Hernández-Pajares, Technical University of Catalonia, Spain. |

| Level | Intermediate |

| Year of Publication | 2011 |

According to the Newtonian mechanics, the equation of the motion of a mass [math]\displaystyle{ m_2 }[/math] relative to another mass [math]\displaystyle{ m_1 }[/math], considering only the central attractive force between them, is defined by the second order homogeneous differential equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{\mathbf {\ddot r}}+\displaystyle\frac{\mu}{r^3}\mathbb{\mathbf r}=\mathbb{\mathbf 0} \qquad \mbox{(1)} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{\mathbf r} }[/math] is their relative position vector, [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=G(m_1+m_2) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is the universal gravitational constant. In the case of motion of an artificial earth satellite, its mass can be neglected with respect to the mass of the earth (i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \simeq G M_e }[/math]).

The integration of this equation leads [footnotes 1] to the Keplerian orbit of the satellite:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{\mathbf r}(t)=\mathbb{\mathbf r}(t;a,e,i,\Omega ,\omega ,\tau ) \qquad \mbox{(2)} }[/math]

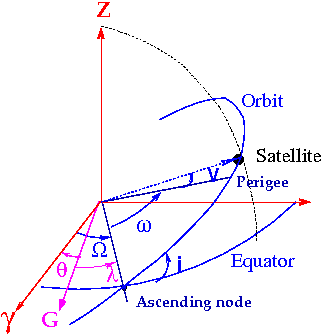

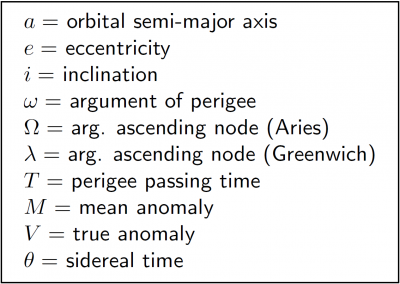

defined by the following six orbital parameters [footnotes 2] (see figures 1 and 2):

- [[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math]] Right ascension of ascending node is the geocentric angle between the ascending direction and the Aries point directions. Note: The intersection of equatorial plane and orbital plane is called Nodal Line. Its intersection with the unit sphere defines two points: the ascending node, through which the satellite crosses to the region of the positive Z-axis, and the descending node. Right ascension ([math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math]) is measured in counter-clockwise sense when viewed from the positive Z-axis.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]] Inclination of orbital plane is the angle between the orbital plane and the equator.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math]] Argument of perigee is the angle between the ascending node and perigee directions, measured along the orbital plane. The perigee is the point of closest approach of the satellite to the centre of mass of the earth. The most distant position is the apogee. Both are in the orbital ellipse semi-major axis direction.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math]] Semi-major axis of orbital ellipse is the semi-major axis of the ellipse defining the orbit.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math]] Numerical eccentricity of the orbit is the eccentricity of the orbital ellipse.

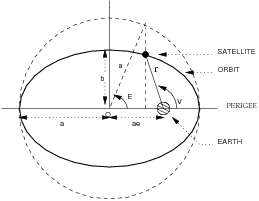

- [[math]\displaystyle{ T_0 }[/math]] Perigee passing time is the time of the satellite passage through the closest approach to the earth (perigee). Satellite orbital position can be obtained at a given moment [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] using [math]\displaystyle{ \tau=t-T_0 }[/math] or any of the three following anomalies (see figure 2):

- [[math]\displaystyle{ v(t) }[/math]] True anomaly is the geocentric angle between perigee direction and satellite direction. The sum of the true anomaly and the argument of perigee defines the Argument of Latitude. Notice that for a circular orbit ([math]\displaystyle{ e=0 }[/math]) the argument of perigee and the true anomaly are undefined. The satellite position, however, can be specified by the argument of latitude.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ E(t) }[/math]] Eccentric anomaly. Given a line that is normal to the major axis and pass through the satellite, it defines a point when intersects with a circle of radius [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math]. Then, the eccentric anomaly is the angle (measured from the centre of the orbit) between the perigee and such point.

- [[math]\displaystyle{ M(t) }[/math]] Mean anomaly: It is a mathematical abstraction relating to mean angular motion.

Figure 1: GNSS satellite orbital elements

The three anomalies are related by the formulas, see figure 2:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{l} M(t)=n(t-T_0) \\ \\ E(t)=M(t)+e\sin E(t)\\ \\ V(t)=2\arctan \left[ \sqrt{\frac{1+e}{1-e}}\tan \frac{E(t)}2\right]\\ \\ n=\frac{2\pi }P=\sqrt{\frac \mu {a^3}}\\ \end{array} \qquad \mbox{(3)} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] denotes the mean angular velocity of the satellite, or mean motion, with revolution period [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]. Replacing [math]\displaystyle{ a=26\,560\; km }[/math] (nominal value for GPS satellites) in the last of the above equations, an orbital period of [math]\displaystyle{ 12 }[/math] sidereal hours is obtained [footnotes 3]

Notes

- ^ The solution of this equation can be found in any text book of celestial mechanics, or satellite orbital motion, as well.

- ^ We restrict ourselves to elliptic orbits.

- ^ A sidereal day is [math]\displaystyle{ 3^m\,56^s }[/math] shorter than a solar day (see section Time References).